Robert Bates, Head of Claims, investigates the risk creep for insurers from the substantial increase in turbine size.

Around every three years, turbine suppliers release new technology platforms. Each new platform has one thing in common: more power. More power means fewer turbines are needed for a given project output, meaning fewer components to install and less balance-of-plant (e.g. foundations and array cables), resulting in a lower installed cost per megawatt. Each new platform delivers a targeted reduction in the levelized cost of energy of the output.

The relative change in blade length is often missed. For a given wind speed, to generate more power a wind turbine’s swept area must increase (i.e. the blades must be longer). The latest platforms go one step further: the blades are longer than they need to be for maximum power – also known as nameplate capacity. (Keep in-mind that the turbine can only generate the maximum power of the power offtake equipment: gearbox, generator etc.) Instead, they are optimised to increase the energy produced by the wind turbine over the lifetime.

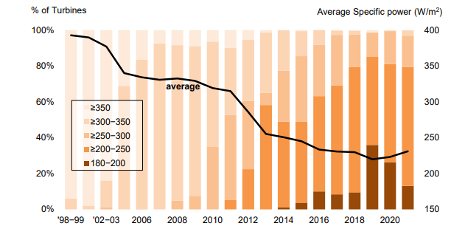

Specific power is the term to describe this trend. Measured in watts per square meter, a lower specific power means less power for the given swept area of the turbine. By having longer than necessary blades for maximum power, it leaves the turbine able to generate more power at lower wind speeds. By capturing more energy at lower wind speeds, a wind turbine can increase its capacity factor over the long term. This makes low wind speed sites economical.

Figure 1: Specific power for onshore wind turbines in the U.S.

So what will the implications of larger turbines be for insurance? While bigger machines means fewer of them for a given project size, each turbine costs more. With bigger components come bigger values per turbine. All else being equal, underwriters could simply charge the same rate on a larger per turbine sum insured and receive adequate risk premium for the new technology. All else is not equal, however, and there will be other consequences for insurance beyond bigger premiums driven solely by increases in values. After all, it’s feasible that a new 100MW project comprised of 20 5MW turbines will have a lower total insured value than one comprised of 100 1MW machines, due to reduced installation costs. (It’s likely other factors, such as higher subsidy regimes in the past, will mitigate the effect of this somewhat.)

There is growing acceptance that deductibles should increase – to some extent! – to correspond with the increase in value. A 5,000 euros deductible on a turbine worth 5,000,000 euros is essentially meaningless. But lenders, sponsors and developers will not tolerate deductible increases without justification. Insurers have a habit of punishing innovation with unnecessarily high deductibles, of pushing as much risk as possible onto developers when new technology emerges. It should be borne in mind that the newer, larger turbines represent an incremental evolution of existing technology – not a wholesale revolution.

We expect narrower defect coverage for new equipment compared to tried and tested technology – especially if any of it could be described as ‘prototypical’. The renewable energy market typically relies on the London Engineering Group Defect Exclusions, with LEG 1/96 being the narrowest form of coverage and LEG 3/06 the widest. Truly prototypical technology will only get LEG 1. But as most of these turbines already have the requisite 8,000 operating hours, and type certificates, LEG 2 is usually available. Bear in mind, however, that LEG 2 can be unsatisfactory for offshore wind projects, where arguably it excludes the access costs that form the majority of claims. (A WELCAR Defective Part regime is preferable.) Insurers seek to impose coverage restrictions on new technology because faults (if there are any), like serial defects, are probably going to emerge during the first couple of years. With a longer track comes greater comfort.

Logistical challenges posed by bigger and heavier equipment may also drive wording and pricing changes. Transporting 75m+ long blades is a huge challenge. Should these, therefore, be split into sections? But then any joint made at site will be a weak point in the blade, likely increasing the risk of blade throws and detachments. Likewise, towers have been produced and transported in cylindrical sections for many years. But now, the diameter of some designs is so large they cannot be transported on roads because they won’t fit under bridges. This has led to ‘segmented’ designs of two more portions of tower sections (imagine the arc of a semicircle, as if the cylinder had been vertically chopped in half). This increases the complexity of design and again, introduces weak points more vulnerable to failure than factory-made joints. We may see increased marine cargo and inland transit deductibles to take this into account. Moreover, there are fewer cranes capable of lifting large, heavy components 80m+ in the air, which could extend downtime in the event of a claims if a crane can’t be found. If the supply of cranes does not keep up with demand, we could also see longer DSU and BI deductibles.

One more ‘metaphysical’ change to think about is the greater concentration of risk. A big attraction for conventional energy and power underwriters looking at renewables has long been the greater spread of risk presented by lots of small generating assets, compared to one or two very large ones. If one wind turbine fails at a 100 turbine project, you only lose 1% of the project’s revenue; if a turbine fails at a conventional power plant, you could lose over half. Wind still poses a much lower single point of failure risk than conventional power, but the difference is no longer as stark as it once was.

New technology will help us achieve our decarbonisation targets more quickly and effectively than sticking with tried and tested equipment. Underwriters know this, and most want to support the roll-out of better equipment. They can only do this, however, sustainably – i.e. profitably – and without exposing their capital providers to undue risk. With a team comprised of ex-underwriters, experienced brokers and qualified engineers, we can support our clients build innovative tech with bankable terms and conditions by bridging the knowledge gap with insurers, ensuring a fair balance of risk sharing for the future of renewable energy.